The Myth of Madness

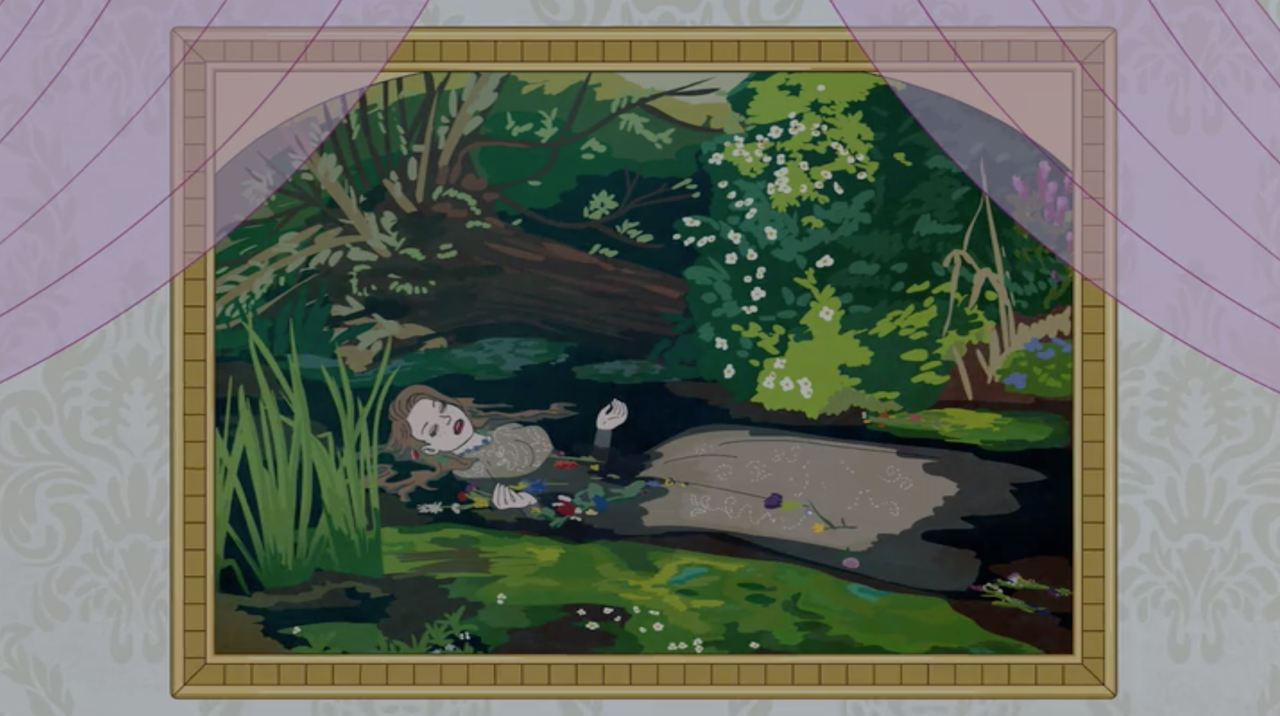

Ophelia, John Everett Millais, 1852

My favorite time of the week is Monday, 5:00 pm–7:00 pm. I teach Branding and Design History in the Master of Design, Brand Design, and Strategy program. The students are intelligent, insightful, curious, eager, and professional. As any instructor knows, students who want to be in a class are gifts.

It’s also exciting to reframe history through the lens of brand strategy in the broadest sense: provenance, ownership, economics, politics, and cultural issues. The course has more to do with people, historical events, and technology than a nifty logo. Researching Roman amphorae and oil lamps sounds rather less than thrilling, but who knew identifying stamps and markings could indicate the role of women in business in ancient Rome or economic trends and trade? I know you’re asking; did he say “exciting”?

The graduate students in the course are polite and allow my odd connections. For that, they are earning lifetimes of good karma. When we discussed the Arts and Crafts movement and branding (yes, this is relevant today), I veered off into John Everett Millais’ 1852 painting, Ophelia. See how this post moved abruptly from a graduate course of study to a painting?

Ophelia is sublime. As in the painting, although the character is also. It depicts a typically off-stage scene of Ophelia drowning in Shakespeare’s play Hamlet. Ophelia, mad with grief, has been making wildflower garlands by a brook. She climbs onto a willow tree, dangling the garlands, and the branch breaks. In the water, she floats singing, unaware or not caring that her clothes are filling with water and she is sinking.

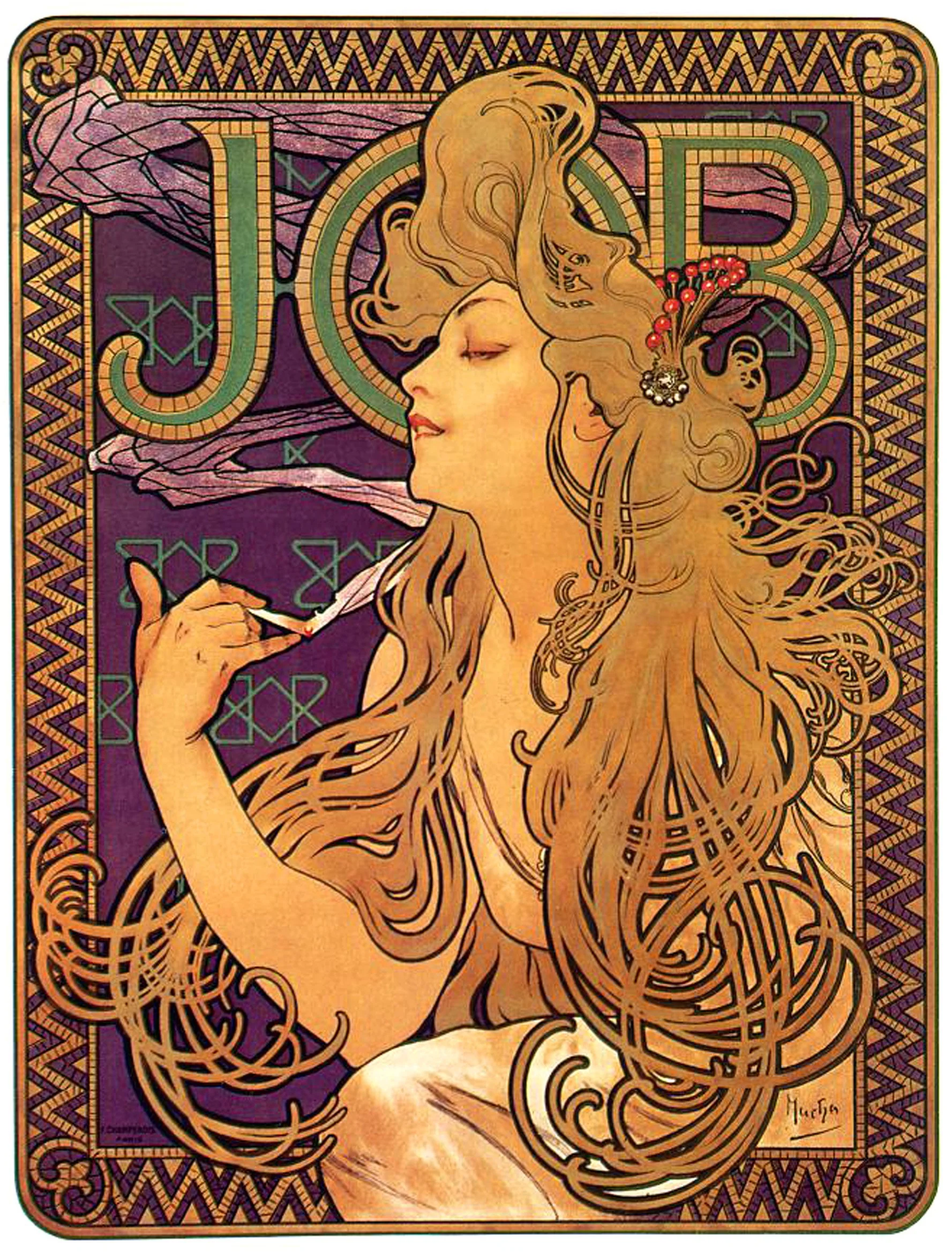

The painting falls within the Pre-Raphaelite movement focused on the natural world, detail, and vibrant color. Ophelia’s face is pale and simple, contrasting with the detailed elements surrounding her. This is a common technique in Alfonse Mucha and Bob Peak’s work. Obviously, there is an enormous amount of subtext here connected with the role of women in the Victorian era, sublimation, death and nature, sexuality, and the male gaze. The overt message is a romanticized view of madness.

What I find intriguing is the multiple references to the painting in art, photography and film. At times it is oblique such as the scene in The Hours (2002) with Julianne Moore’s character, trapped in the conformity of the 1950s, “drowns” on a hotel bed contemplating suicide. And in the same film, Nicole Kidman, as Virginia Woolf, drowns herself in the river.

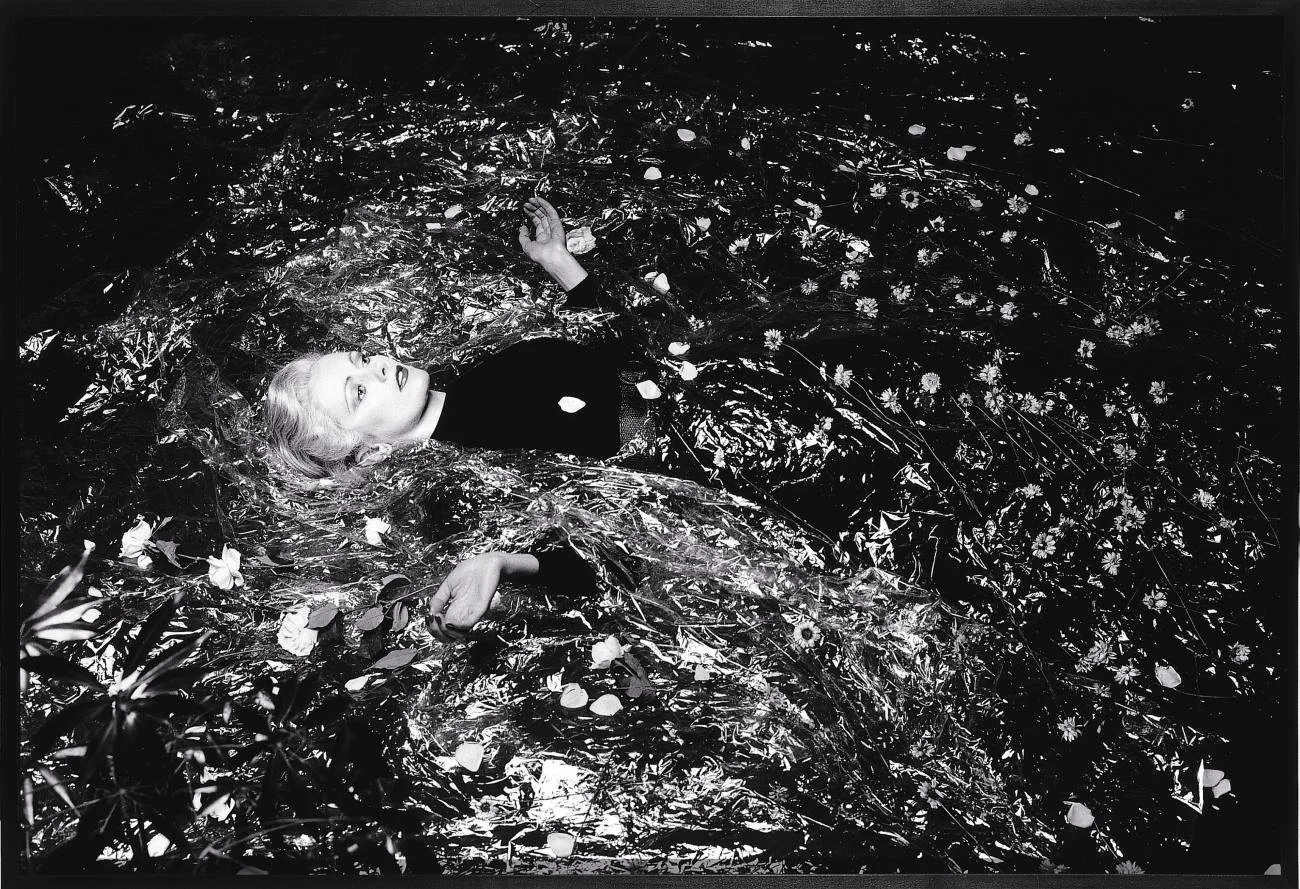

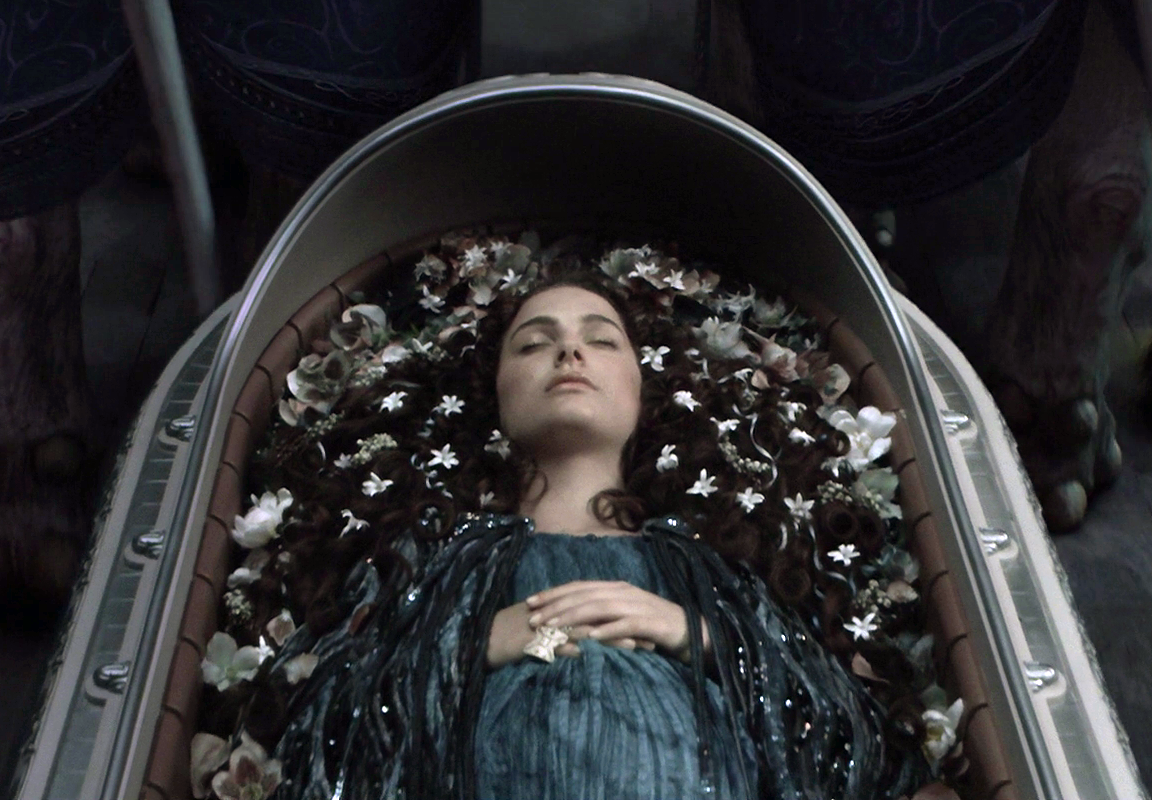

Victor Burgin’s masterful The Bridge (1984) recreates a scene from Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo referencing Ophelia. In Vertigo, Kim Novak’s character Madeline, seemingly mad, throws herself into San Francisco Bay. The Millais painting pops up when least expected. Padmé Amidala’s funeral in Star Wars Episode 3 - Revenge of the Sith (2005), Princess Aurora in Maleficent (2014), and Kirsten Dunst in Lars von Trier’s Melancholia (well that was kind of expected).

But my favorite is the reference in Claire McCarthy’s Ophelia. In this version, Ophelia, played by Daisy Ridley doesn’t go mad and drown, but lives.

The Bridge, Victor Burgin, 1984

Vertigo, Alfred Hitchcock, 1958

Hamlet, by William Shakespeare (1604), spoken by Gertrude

“There is a willow grows aslant a brook

That shows his hoar leaves in the glassy stream.

There with fantastic garlands did she come

Of crowflowers, nettles, daisies, and long purples,

That liberal shepherds give a grosser name,

But our cold maids do “dead men’s fingers” call them.

There, on the pendant boughs, her coronet weeds

Clambering to hang, an envious sliver broke,

When down her weedy trophies and herself

Fell in the weeping brook. Her clothes spread wide,

And mermaid-like a while, they bore her up,

Which time she chanted snatches of old lauds

As one incapable of her own distress,

Or like a creature native and indued

Unto that element. But long it could not be

Till that her garments, heavy with their drink,

Pulled the poor wretch from her melodious lay

To muddy death.”

“There is a willow grows aslant a brook

That shows his hoar leaves in the glassy stream.

There with fantastic garlands did she come

Of crowflowers, nettles, daisies, and long purples,

That liberal shepherds give a grosser name,

But our cold maids do “dead men’s fingers” call them.

There, on the pendant boughs her coronet weeds

Clambering to hang, an envious sliver broke,

When down her weedy trophies and herself

Fell in the weeping brook. Her clothes spread wide,

And mermaid-like a while they bore her up,

Which time she chanted snatches of old lauds

As one incapable of her own distress,

Or like a creature native and indued

Unto that element. But long it could not be

Till that her garments, heavy with their drink,

Pulled the poor wretch from her melodious lay

To muddy death.”