Delusions of Grandeur

My grandmother was born in 1901. While she didn’t live in Virginia before the civil war, she told stories about her grandfather and his bucolic existence. In her world, everyone was kind, gentle, good, and came from good families. When she talked about emancipation, she remained unmoved, telling us, “Well, after granddad freed his slaves, why they refused to leave. They loved him so dearly, they all cried, ‘oh, please let us stay.’” My brother, sister, and I tended to look at her and not know what to say. So we politely nodded with frozen, terrified smiles. It never occurred to her that they these people had been held in bondage for two hundred years, had little education, no prospects, or anywhere to go.

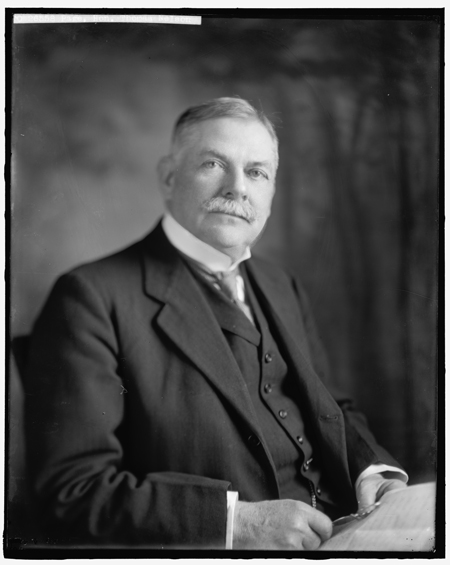

I’ve been reading a biography of another family member, Thomas Nelson Page. Like my grandmother, he seemed to live in a dream world. Page was a well-known author, who wrote books that promoted the idea of, once again, a romantic antebellum American south, filled with chivalry, fine ladies, and happy slaves. Page was 12 years old when the civil war ended. He was born at Oakland Plantation in Virginia. He was descended from two prominent families, Page and Nelson. Like most Virginia gentry, he was related in multiple ways to most of the other gentry.

I can understand how seeing life before the war as a child, and then facing the destruction and upheaval during and after the war could color his perception. He could not grasp the full ramifications of slavery. In other ways, Page saw the reality. Old Virginia was ruled by a small group of the aristocracy, and after the war replaced with a moneyed, capitalist class where family names had little value. His world and its benefits had collapsed. As it had for many others, including my grandmother. So they retreated into a past that was kind, and slavery was justified as a paternalistic obligation.

This is what I find difficult to understand: Page was enormously successful in the North. His book, Marse Chan (Master Channing), was a best seller, as well as other antebellum nostalgic novels, In Ole Virginia, Two Little Confederates, and The Old Gentleman of the Black Stock. The concept of a great broken civilization, and the lost cause, played out repeatedly in popular culture. This Moonlight and Magnolia style culminated in Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With The Wind. The lesson here, then, has something to do with self-delusion, or a way of ignoring all facts to embrace a preferred history.

Before my grandfather died, he called me over, “You see, Sean, there is something wrong with your grandmother in the head. She can’t understand that we are on a railroad journey.” In reality, they were at home, but my grandfather was convinced they were traveling by rail around the American west, and somehow the US Post always found them. He was sure his worldview was correct, and my grandmother was wrong. How many of our own perceptions are delusions? Maybe I’m not actually going to work each day, but sitting in a sanitarium somewhere.