The Time Machine

MOO recently did a survey on handwritten communication. It turns out that 56% never sent anything handwritten. Forty-one percent valued handwritten letters over digital, and fifty-one percent never threw out the handwritten notes. So we thought it was about time to print a batch of postcards with MOO. I like the MOO people; they understand paper and design. They make the beautiful, heavy, wonderful cards like the one in American Psycho.

Call me a materialist, but I like things. I like to keep things. I don't have a little box of websites, but I have one with letters, cards, and bits of paper.

Why do we care about these sheets of paper? They define us. They tell us who we are and where we came from. Not surprisingly, I have copies of many letters written by family members, the originals long ago donated. These letters tell me these things: work hard, be prudent, serve your country, and you'll never be as good as we were in the 18th century. They aren't beautiful. They don't have fabulous handwriting. But they have survived and have the power to help me determine who I am.

When my distant grandfather, Dr. Thomas Walker, sent a letter and marriage agreement to his first wife's cousin, Elizabeth Thornton, I doubt he thought I would read it 240 years later. There is a note from Thomas Jefferson, appointing his guardian and father's best friend, Dr. Walker as a Captain during the Revolutionary War. Another letter serves as a legal document signed by Elizabeth Thornton's cousin, Meriwether Lewis and annotated by William Clark a year after Lewis was murdered or committed suicide. These items transcend their physical presence and describe the complexities of relationships that I could never find in a history book.

I find two letters rife with unstated content. In 1863, in the midst of the Civil War, while her southern culture was collapsing, Mary Walker Cabell created a family tree to share with another cousin. There is something more here than a genealogical study. This is an attempt to capture Cabell's history and values and preserve them for others. She was raised in a world of privilege and her status in society was clear. Now, as this life disappeared, she used pen and paper to anchor herself to another time.

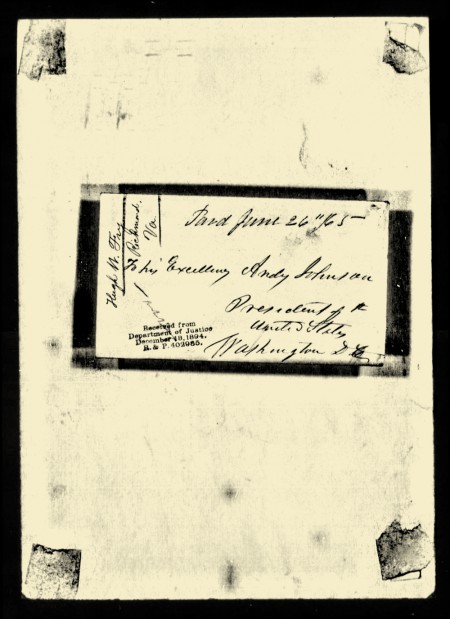

The correspondence that carries the most emotional weight, however, is a note from Hugh Walker Fry in 1865. After the war, Confederate leaders and wealthy planters needed to apply for a pardon to restore their American citizenship. The letter itself is mostly boilerplate wording, but the exterior of the letter, addressed to "His Excellency Andy Johnson" is the most salient part. Andrew Johnson was the President of the United States. Did Fry intend "His excellency" as a slur or was he simply unaware of proper protocol when addressing the President? Again, his fortune was lost and way of life radically changed. What is left of this dramatic and intense experience is a piece of paper with three words.

These written letters may have seemed irrelevant, or simply part of everyday life, when created. But due to their intense personal connection and the evidence of the writer's own hand, they serve as a time machine.